I am often asked about apprenticeships in craft and want to share some thoughts and experiences.

To many the word apprenticeship conjures a picture of a young person working for several years alongside someone with a skill, slowly learning the trade themselves. Some of the most amazing people I have met are folk that went through traditional engineering apprenticeship, they just understand how to handle materials and manipulate them in all sorts of ways. They understand what tolerances things need to be made to for particular jobs and how to work to tolerances of a fraction of a mm when needed. The apprentice would start on a low wage which would gradually increase as they became more useful. At the Heritage Crafts Association’s annual conference we heard wheelwright Greg Rowland talk about his experience taking on just such an apprentice. In the first year his business turnover went down 20% because of the time he had to devote to training. In the second year his turnover was still down but now only by 15% and after the third year his turnover was up by 40%. This gives a fair impression of the impact on a business of taking on an apprentice.

Apprenticeship today in the UK has generally come to mean something quite different. Apprenticeship is still about young people supposedly learning on the job but the largest single apprenticeship employer is McDonalds who take on nearly 10,000 government subsidised “apprentices” each year. In the first year of an apprenticeship the “trainee” can be paid as little as £3.50 an hour. At the end of a weeks work that would give them about £100 out of which they have got to travel to work, clothe themselves and feed and house themselves. Even if they are living at home they are still not going to have much of a social life. So when you hear the government talking about having created half a million new apprenticeships a year, don’t imagine old fashioned engineering apprenticeships learning fantastic skills for life, picture instead someone working somewhere like McDonalds for £3.50 an hour.

Through my work with the Heritage Crafts Association we tried hard to work with Government to set up an apprenticeship scheme that would enable genuinely skilled craftspeople to pass their skills on to the next generation but the training that takes place in the workshop is not recognised as valuable training, everything that happens in the workshop is perceived as work that needs to be paid b the employer. It is only the day release work they do at college which is regarded as training for which there are government subsidies (£1500 a year) to cover.

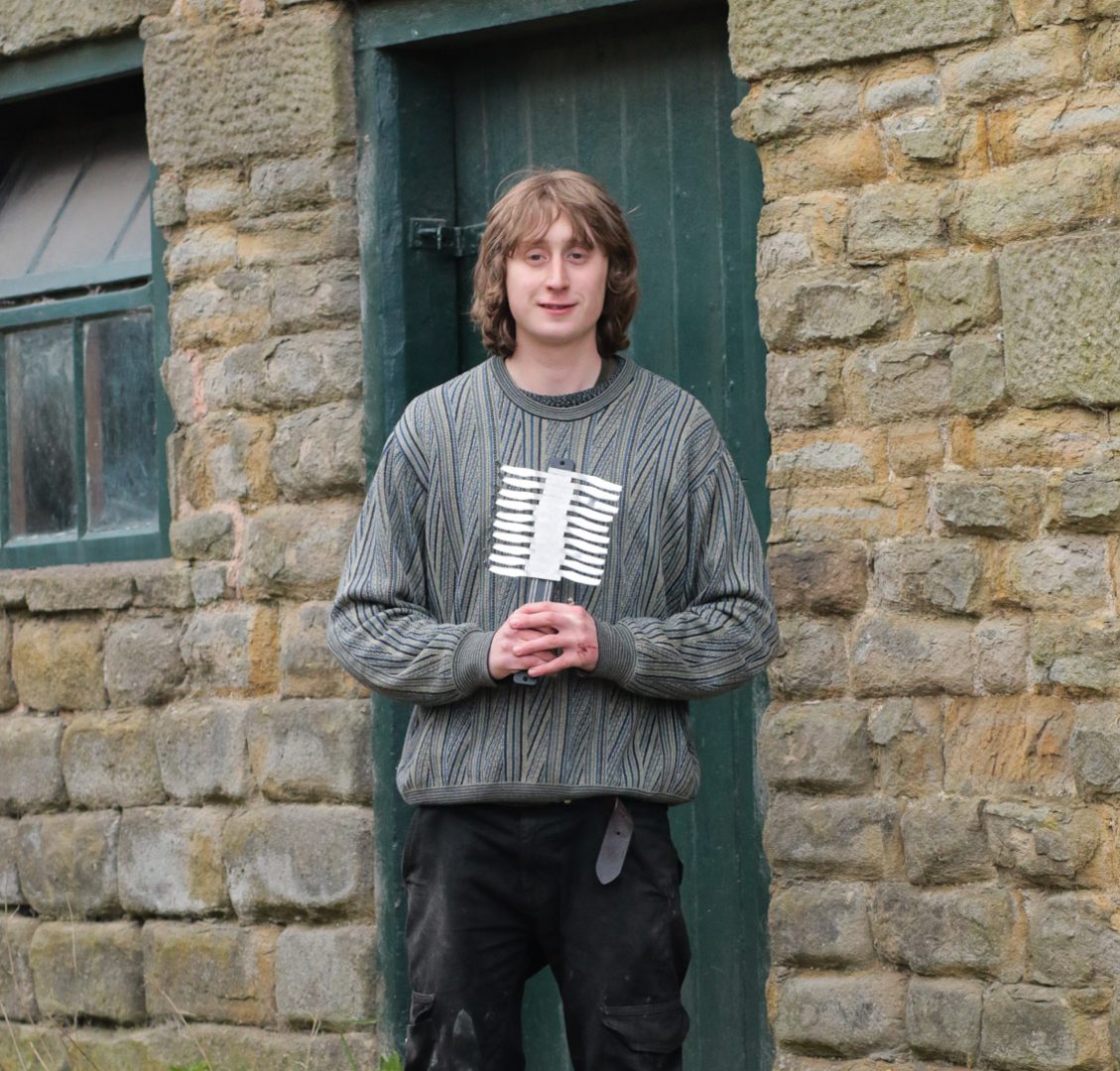

Anyway back to my own situation. This is my “apprentice” Zak.

I remember talking with Saddler Frank Baines who has had a lifetime of training apprentices. He told me to avoid folk who wanted to come from the other end of the country to work with you because they were passionate about the craft. They would stay just for two years or so until they had learnt what they needed then they would be off to set up their own business. If you look at Greg Rowland’s experience that is a serious drain on the viability of the business. Instead Frank told me just take on some local lad that wants a job, they will learn to love the craft, it comes naturally. So Zak lives in the village and is good friends with my son. He started helping me pack mail order parcels in the run up to Christmas 2 1/2 year ago. We got on well and he fancied having a go at helping me with my toolmaking so I stated to teach him. By the following May I took him on full time. I looked at the various “apprentice” schemes but frankly they appear to be just ways of massaging unemployment figures, getting people off the dole and into very very low paid work. I could not bring myself to employ anyone at £3.50 Zak started on £7 an hour with holiday pay and sick pay.

We had two other speakers at the HCA conference Lisa Hammond and her apprentice Florian Gadsby. Florian told of how when he started throwing pots Lisa would look at a board of 20 and pick out 2 that were good enough and the rest went back in the pug mill. So it was when Zak started grinding knives. Out of each batch of 20 there would be 3 or 4 that could be sold and a lot of seconds. We don’t have a pug mill and the blade blanks cost several pounds each so it’s a potentially expensive game learning to grind properly.

Anyway fast forward to the present and Zak is now an extremely competent grinder. We just did his second annual review and raised his wages again to £10 an hour. He is now really contributing to the profitability of the business but he is still learning a lot. He has recently finished the first batch of knives that he made entirely himself from taking the rough blank and forging the bend, grinding, honing and polishing and fitting the handle. On Monday he spent the day helping Brian Alcock the last full time self employed grinder in Sheffield who grinds all our axes. It gives me huge pleasure to see a 20 year old sat alongside a 65 year old with the skills being passed down.