I’ve learned that woodworking is much more than merely working wood or just, well, processing it: that’s for a percentage of people that is. More those who enjoy touching working the material I suppose. You know, taking material from a tree and making something substantive from it and recognising its background in its growing vibrancy somehow. And by substantive I don’t necessarily mean big in terms of project mass but perhaps something quite substantive by the level of its demand on us as makers. Through the decades I’ve suggested that machine making is not the same as hand making. Meaning the two realms of hand work and machine work are nothing in any way like each other and so the two very distinct realms should only be compared in the same way an apple is compared to an orange––both growing on trees, are round, vary in size and have skin. But the tastes and textures are very, very different. In essence, each is exclusive of the other. I feel the same way about machining wood and working it with hand tools. The methods of working make the two realms diametrically opposed to one another. Even so-called hybrid woodworking is not unifying. As it is with the illusion that people think that they can multitask, primarily it’s only task prioritising. Some people can do it well and some cannot. To suggest that half the world’s population multitask and the other does not has always been silly. So I see many reasons that machining wood can never really be more than the wood connection rather than the processes of working it.

Critics do occasionally accuse others of snobbery, exclusivity and more if and when they advocate only one way rather than another or that one is more skilfully executed than the other. But that often happens when truth causes others to take offence even when no offence is intended in any way. A well-designed spice rack with sliding dovetails for instance could be as technically, mentally and even physically demanding as a timber-framed building or a garden shed, a coffee table or a bookshelf. What can make the difference is the equipment availability. Of course, in my case, I am talking about hand-making rather than something needing crane lifts, tenoning machines and mortisers.

I have lived just about long enough to witness great changes in woodworking made by small incremental changes. In my lifetime I have gone from seeing just about every woodworker I ever encountered ditch using 95% of hand tools, well maintained and cared for for decades, to become so-called “power tool junkies”. Through the brief transition, machine-only makers have little concept of hand tools and their workings and most no longer know how to sharpen a chisel, a plane or a handsaw by hand.

I watched small, family-run DIY shops on street corners and the high street become subsumed by massive conglomerate chain-store suppliers who priced them out over a five-decade period. Now these small entities offered much more than supplies of DIY and wood. Mostly run by experienced time-served joiners, they offered free advice and guidance along with practical suggestions as to processes and materials to any and all who came in. They also delivered wood cut to size to your door when the shop closed in the evening and even took a look at what you were building.

But in recent decades, the last one in particular, a wide range of new technologies have come in at pace. Seeing the transformation of woodworking as a craft once fully performed by skilled artisans working with traditional hand tools, the men of the day, become a hobby with only hand tools in the middle of the last century to woodworking as a machining process only today, I found myself pondering change. I couldn’t help but wonder if a new phase was upon us, a phase following where hobbyists enjoying the developments in fields of CNC woodworking even for home use could shortly be primarily engaged with their wood using AI alongside the continually evolving CNC processing to make their next coffee table or spice rack. I know, that might seem less likely than likely, but is it too much of a stretch? This thought of redefining woodworking where the new so-called woodworker sends a key-tapping request to the garage workshop two metres away next door and the new robotics could be directed to extract wood (or even make it) and load it into the CNC devices to twist, spin, align and reorient the material into the five rotating cutterheads to have a variety of different wood cuts made to replicate or even reinvent the woodworking joints used to make your coffee table for you. Perhaps grain itself can be colour-coordinated along with grain patterns and configurations for perfect book-matching, things like that. Grain density might be optimised according to task or outcome requirements simply by sonar sensing and a wide range of hitherto unavailable options introduced.

In a recent, brief exchange, I commented that if I were to make a dovetail joint by machine it would for me be a fake make. Now, of course, that is for me because I will never need to make a dovetail using a machine like a power router and such. I decided to make a more careful and considerate alteration to the text so as not to judge others or indeed have others feel judged in some way as to whether their joint if made by machine was any less of a joint than a hand-made one. Of course, it is not: the joint whether made by hand or machine is still, at the end of the day, a fully-fledged dovetail joint and both are of equal worth with regard to the final outcome in their mechanical attributes of strength and functionality, longevity, etc. Whether made by hand or by machine, the joint is in and of itself still a real dovetail joint. The difference for me and many is that on the one hand, the joint is developed and cut by a machine substituting for and designed to replace hand skills whether hand fed to the wood or the wood hand fed to the machine and not by a person manipulating a range of uniquely different hand tools to the wood and uniquely controlled in every way by the innate senses and training of the person applying the tools (and a machine is a machine and not a tool in the sense of which I speak) and their cutting edges to the wood. And it’s this simple fact that makes all of the difference in the world.

And, of course, I realise that this can be controversial if 98% of all woodworking now, whether by so-called professionals or amateurs, is done so by using machine-only methods. Do we become some kind of lesser woodworker if we choose machine cuts to do most if not all of the sizing and fitting work for us? I really don’t think so. I think we cannot compare apples to apples here. In some ways, when you think about it, both can well be considered the more advanced way depending on which paradigm you look from. The test of a person’s skill is, well, very different according to the methods used. I think hand-cutting joinery is the most high-demand form of working wood I know of that there is. On the other hand I understand highly complex work programming requires skills and knowledge I don’t have any clue of and the demand for these users is indeed the inclusion of computer work itself with the machines the computer controls. So that does not mean that setting up CNC machines and developing code is any less demanding, interesting and, yes, fascinating too in its own way. But most such equipment is already set up for the user to plug in and programme according to task. My engineer friend across the way set up his CNC to cut my latest prototype dovetail template in metal and in just 20 minutes the machine ejected six perfect specimens fully saleable and accurate in every way to within thousandths of an inch of the design specs programmed in.

We make personal choices all the time. Some are designated to involve us the more and some are designated to almost take us out of the loop altogether. The latter might well be to eliminate a person’s involvement and is a good plan for any business to work economically and keep a competitive edge, I am sure. The ultimate goal birthed through the Industrial Revolution was to minimise the need for skilled workmen and women and wherever possible to replace them with machines to produce the goods needed for a global feed into the economy’s insatiable appetite for making money, and are we not still moving constantly along that same trajectory? Is this not the very nature of technology in industry? Objectors then became classified as Luddites––degenerates who hated technological progress. Even though crafting artisans were well in the majority and supported the conservation of a traditional working culture in every craft of the age, there would be no democratic vote for it. It was never a democratic consideration but more a control of the workforce being shunted head-on into the factories that needed cheap, controlled and compliant labour on minimum wage.

Looking now at what has been recently happening in areas surrounding creative arts by those protesting against AI being used to take existing content and copy it with a view to reduce the need for creative artists in their different fields, it seems that it is hoped that AI will systematically replace scriptwriters and every other kind of artist there is. I wonder if these creatives, as in the early 1800s here in the UK, might be classified as today’s Luddites and that we are presently seeing history repeat itself. There can be no doubt that just as the emergence of looms destroyed home working and family businesses we also reduced the cost of goods so much that many feel the need and ability to throw away great clothes because by fashion alone they become ‘worn out‘ or over worn, even after only a few wearings. Without the Industrial Revolution, we wouldn’t have cars, petrol-based products and pollution and nor would we be fighting issues surrounding many geopolitical manipulations and machinations. My insulin needles comprise an amazing array of amazing elements ranging from glass moulding, plastic parts, printing in the round and stainless steel needles so fine I cannot feel them enter my arm, stomach or legs. There can be no doubt that life has been enhanced by technological developments. I will park that there.

Lastly. Riding my pedal-only-powered bicycle demands total engagement with the beautifully paved road through a series of gears easing the passage on the hill climbs and into the head-on winds. Though a derailleur-geared ride, the energy expended is still the same only instead of a hard drive in heavier gear I can choose ten times more rotations using an alternative gear to match the opposition. On the other hand, I also use a hybrid bike for more off-the-road rides and this bike, an assist-powered electric version, though it must always be pedalled, is a totally different ride. The difference is simple. I can have the support of electric for a full 130-mile ride up hills and down dales where the hills and winds seem barely to exist. On my one bike, the work is much harder so I use this one on more localised rides to the shops and such but also for short bursts of twenty-minute exercise when I feel I need it. The electric bike takes me longer distances in about a third to half the time. If I can afford the time to take longer rides to different places solely and primarily to enjoy the different elements of cycling and scenery in my ride or go to other places I might choose this bike over the other. Now, of course, both bikes give me exercise and both get me where I want to get to and it’s my choice. In like kind I can also use my bandsaw for much of any resawing I need. This is especially handy when it comes to going through say 8″ oak, knotty elm or wiry other woods or indeed any wood that thick. This again is a matter of choice for me but mostly it is energy- and time-saving in my very full-on days as a full-time maker nearing his mid-seventies.

I need to pace myself the more these days and rely on stamina support on some days. In the case of a younger maker, they too might be more time-strapped and therefore need to rely on a machine or two here and there and now and then. Choices choices, choices. The question for me is whether skill development delayed will ever come if it is always a question of your choosing speed. It doesn’t take 58 years to develop the skills and speed and knowledge I have. And it is easier to learn today than ever in the history of woodworking because we have the internet. The issue in any excess, as we have seen through industrialism, is finding what we really need and finding it when we need it. I doubt that anyone can really cut a dovetail with much gain using a power router and jig than I can if we both start from scratch with wood prepared but both needing set-up time included in the trial. On average, I take 20-30 minutes to make a dovetailed corner accurately. Even if the power router halves that time it is not much of a gain. Where people gain is in having a half-decent-looking dovetail from the machine when done. Where they lose is never gaining dominion over their lack of skill using hand tools, mastering sharpening chisels, planes, saws, card scrapers and then too #80 cabinet scrapers. We woodworkers in our garages are really only likely to cut half a dozen of one size for any given project and will never mass-make anything so it’s unlikely that we would invest in the the mass-making equipment cited above. Furthermore, Luddite or not, you will never see me use a power router with router bits and dovetail guides to slalom through to make any kind of dovetail. I’ve avoided it but never because I shun technology as the Luddites were and still are accused of but for very many, many good reasons not the least of which is it’s actually too slow for me, too noisy, too messy and too expensive. It’s also dangerous, polluting and for me, totally unnecessary. It is for most people willing to put in the time to become skilful at hand-cutting dovetails. I believe that this is becoming true for those multiple thousands if not millions of brand-new woodworkers who have trained themselves to cut good, tight-fitting dovetails every time with a few hand tools and within an hour or so too. If they can do so so can most people. 98% of doing anything is a made-up mind.

There is no stopping AI just as the Industrial Revolution was and has been unstoppable and I am not in favour of halting progress if progress is indeed what happens. Mostly, as it is with almost everything, it is about balance. Through the decades and centuries, no one really asked the majority what they wanted. Times have changed and in recent years social media has taken the helm for any and all that use it. It’s really a question of determining what you want from your woodworking.

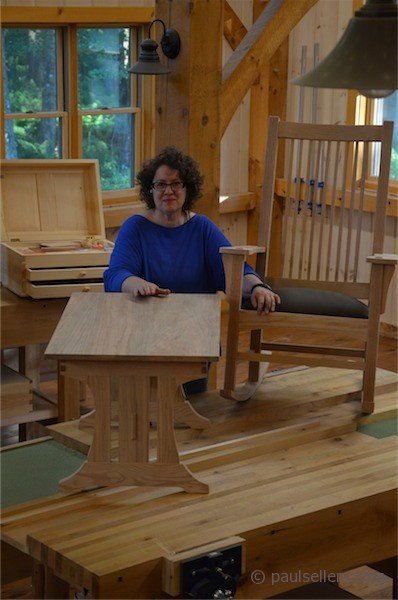

And this is what a dentist nearing retirement looks like when he sits or kneels on the floor to fit an arm to his rocking chair towards the last few days of his month-long investment in learning a craft like mine. Believe you me, if this man can make the tool chest, the coffee table and the rocking chair in three weeks, which he just did and superbly at that, he can make anything you care to name from wood with hand tools and the difference for him is he can still use machines if he wants to.