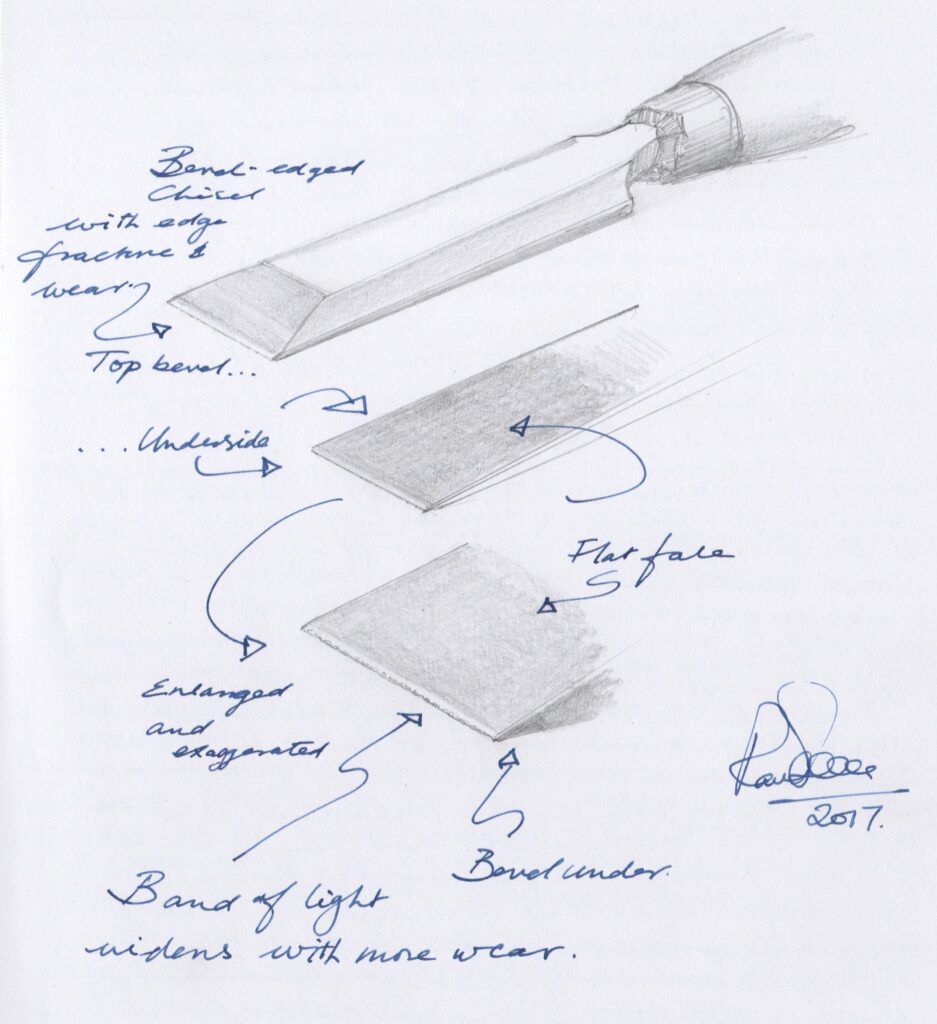

I went ahead and ground a chisel I own that I never grind on any kind of mechanical or electric grinder, never, ever hollow grind, and never grind to then sharpen with two bevels. I stopped doing that back in 1965 when I did it under instruction by a college teacher who failed as a joiner so went on to teach what shouldn’t really be taught, but then I noticed that the men I worked with didn’t grind theirs too often, if ever, either. Phew!

To new woodworkers this morning, I have argued this corner quite often, but never to be argumentative, purely to give good and honest direction. To hollow grind or not to hollow grind––that is the question––whether ’tis nobler. . .

Many will say we have many choices, but for those in the saddle of having to actually earn their living, a go-slow method would never be accepted, let alone tolerated by a watching boss intent on total efficiency there at the bench. In my case, my watching boss was a man called George who cared about my wellbeing and always mentored me to that end. This man went from pare cutting a tenon shoulder, to a sharpening stone, and then back to the shoulder trimming without missing a single step. His seamless deployment of labour and energy became the only example I needed. Since that time, I never came across a faster delivery to a surgically sharp edge anywhere, ever. By this simple and methodical action lasting under a quick minute, I saw the value of time and how the efficient use of it was essential to peaceful working and maximised output.

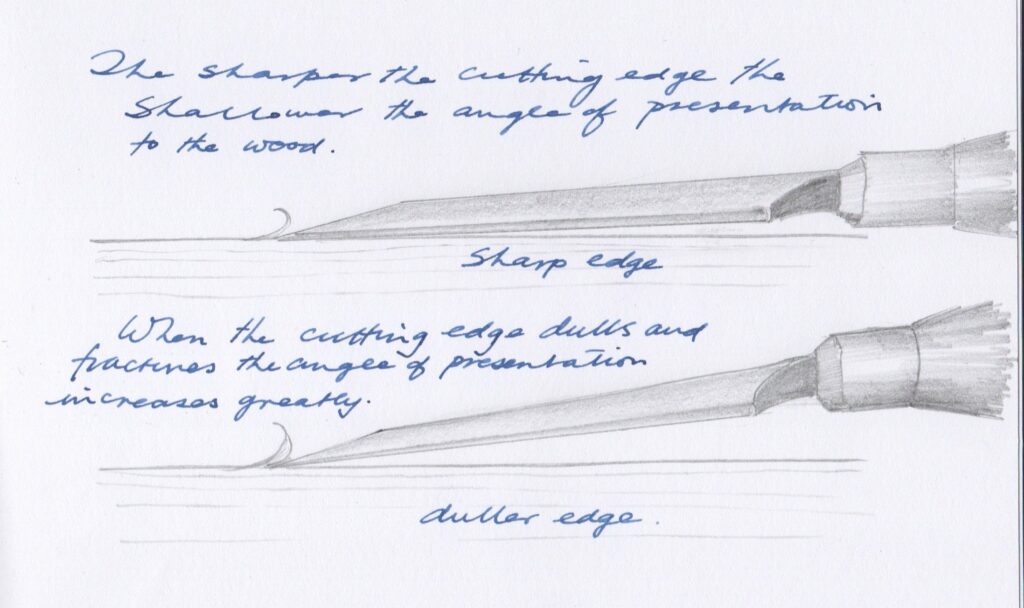

It might surprise you to know that many machine methods will be slower than hand methods. In a time-strapped world where we amateur woodworkers have but a few short hours a week to make, it is really important to use this time wisely. Economy of motion keeps us in the making zone, and that flow of efficiency brings total clarity and functionality without making us part of the machine or putting us on the conveyor belt of manufacturing. When we sense the need for slightly more pressure at the cutting edge we stop, turn, sharpen up and return in a swift, unfaltering movement as though the very act of sharpening the chisel is just as much a part of severing the fibres on the tenon’s shoulder. When we see that, is when we start to gain the insight of mastery.

In our early days of trying to find an answer on how to sharpen an edge, research in the age of mass-information usually takes us down many paths and because of this, the search usually becomes perplexing and thereby exhausting. Eventually, after much trial and error, expensive output, an experiment here and a trial there, we might just find an answer that seems to fit with what we need. Especially will this be so when it comes to simply sharpening the edge of a chisel and a plane. The sharpening of these two tool types is 95% of all you need to learn about sharpening, and these two edges, though the tools are different, are sharpened precisely the same way and without exception. Now, if that doesn’t bring simplicity home, I don’t know what does!

Ultimately, we all develop our own opinions and they usually become our preferences. But, the path to an efficiently produced edge can and does get very muddy. That being the case, how do we find the right path to a keen edge with so many abrasive options to choose from? Thankfully, though often bathed in myths and mystery, sharpening a pristine and surgically sharp cutting edge is not rocket science, but abrasive and abrading is always essential to the quality work we strive to achieve.

So, here is the simple but not simplistic reality we should understand as early on in our woodworking as possible. When newspapers sell news, they must have information to peddle. What they sell is not always true, but the strapline has the bait, and before you know it you are being informed as though they are the font of all knowledge. As soon as selling and making money from it becomes the objective, we should question the truthfulness of it. Sales staff selling tools pretty much copy and paste their information from elsewhere, mostly the manufacturers of what they are selling, but also from just about anything that sounds good to them. Add the strap line, ‘The scary-sharp system’ to selling kits of float glass, abrasive film, honing fluids and so on is baited. Getting to a way that has built in longevity is what we really need. Offering two dozen ways to sharpen an edge isn’t too helpful.

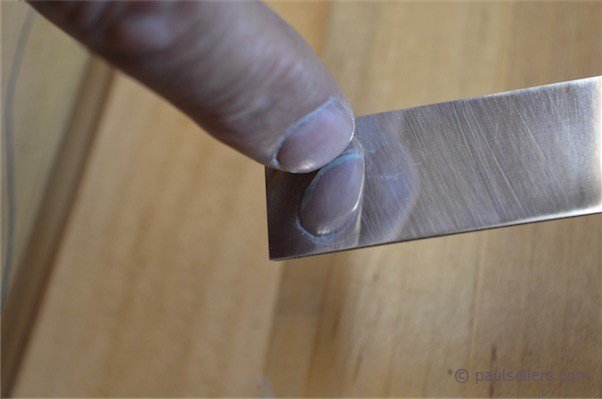

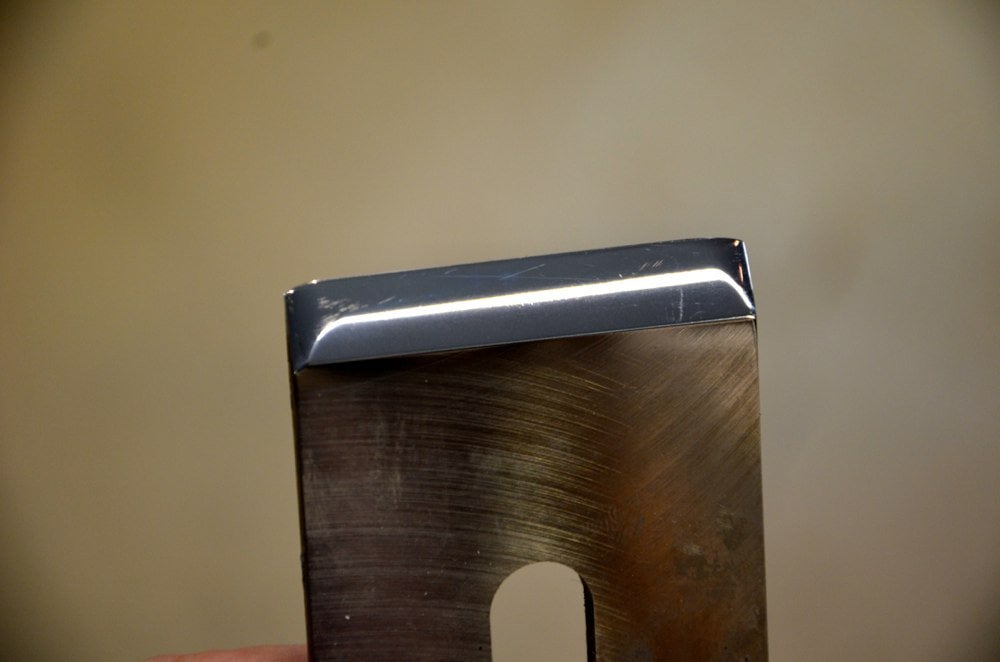

To create a sharp edge, and that is relative, we must abrade two adjacent faces by honing them on some kind of abrasive. Abrasive comes in many forms, but for centuries artisans and peoples around the world relied very much on one type of solid abrasive––rock! Now, rock is just about the most widely distributed resource undergirding our whole world. We can use it as is, or we can create particles of grit from it and attach it to paper to create abrasive paper of one kind or another––hence the term sandpaper. That’s today. In times past, most sharpening came only from solid lumps of rock split or cut into smaller rectangular sections, we then called whetstones. The word whet comes from the Old English hwettan to whet, to sharpen. Though this term is relatively old-fashioned these days, as a boy, the men sent me to get “the whetstone” to “sharpen up.” The list and options for abrading or whetting an edge given today may well give us many choices, but in the age of multiple choices we can suffer from what is known as the pluralist illusion. This multiplicity may seem to give us so many options we can easily be confused, and it’s this can so easily incapacitate our decision-making. We simply cannot choose by physically experiencing all of them, and that leaves us in a ‘don’t know’ place. That being so, we generally rely on what others tell us. Filtering through what is mostly opinion is where we ultimately end up making our decisions. In the 1990s, the advocacy for something called Japanese water stones took hold across the USA. I got the same results very cleanly without any slurry, water-soaked stones and water baths on mats with a black Arkansas stone and two drops of oil in under a minute. Then came the so-called scary-sharp system. New straplines for magazines and sales outlets. Again, my results came from a single stone, and I was back in the saddle.

Through the centuries, on every continent, craftsmen and women have developed their own systems to produce amazingly sharp edges. These edges resulted in cuts that have the ability to sever any and all natural and synthetic materials to enable creative and efficient work. I intend to show the system I use, simply because the abrasive from any source will ultimately cut our steel to develop an edge. It is up to us to decide how much and how little mess we want in our work area. It’s also up to use to determine how much interruption we want to our workflow. My recommendation is to disregard any and all cute sayings and keep realness to the forefront. Headlines and Straplines are intended lures used to draw you into the world of wizard sales outlets of one kind or another. My craft needs no such thing because handwork of any kind has enough fascination of its own. There is no such thing as scary-sharp edges, and edges have always been used throughout the history of centuries. Artisans 250 years ago matched and surpassed anything we have on our hand tools today. How do I know? I look at the results of those tools and the artisan’s accomplishments in that era. No handwork comes close today.

Sharpening is the single most important skill to develop and own but should be the very least intrusive to your working. Many of those new to woodworking with hand tools, and I include seasoned machinist woodworkers not using hand tools, neglect this important task often for days. The sooner you start sharpening, the sooner it becomes intuitive to you, and then the work just gets easier and easier. The good thing is, it’s easy to do. You just need to understand what the goal is.

To get a sharp edge takes no more than a minute’s transition from dull to sharp and on back to the task at hand. That’s what my system has evolved into for me. The abrasive is partly inconsequential until you must replace it, or clean up after it or put it away elsewhere from your working area. This then consumes the most important thing for most of us––time. Four plane irons and half a dozen chisels in different widths, either group, is about four minutes work to go from dull to sharp for me. It’s clean and orderly. But as I just said, the preparation, method requirements, etc can extend the amount of time needed to get to the edge and then the clearing away. My system is the fastest of all long term and the clean-up is almost non-existent. It will take longer to read this blog post than sharpen half a dozen chisels and a couple of plane irons.

My reasons for not using mechanical grinding go beyond the risk of burning the steel and so losing metal as an unnecessary waste––not using one also removes the need for buying a grinding machine. Those with water baths to keep the steel cool, slow grinders passing the stone through a water bath or trickling cold water onto the wheel, have their own problems to deal with, so I will say owning a grinding wheel is great for general aspects of metal working but a definite non-essential for our edge-tool sharpening.

How you invest in your newfound craft often depends on the influence you’ve received from elsewhere or turn to for the information you need. Our world has radically changed in the last two decades, and most of us now turn to Google and YouTube as the primary sources of information. Googling how to sharpen this or that might deliver some good advice, but advice that’s delivered badly or inadequately––and whereas the saying goes, ‘Practice makes perfect.’ it can equally go, ‘practice makes permanent.’ and that can be permanently bad. I tend to avoid woodworking online, even though I use it to promote my own teaching to a global audience I could never reach any other way.

Starting out in something new, we have to question any initial investment. Follow some advice, and you need thousands of pounds in hand tools because the advice generally is to buy the best. The scenario worsens if someone says machines are the only way forward. To get a sharp edge and feel the sharpness in the wood can cost you around £30 and that is what this blog post is about. I’m going to point any woodworkers new to hand tools to our Common Woodworking site here straight off. The information and the tools you really need, together with projects and a mass of other information, where and how to get started, which tools to buy and so on is right there at your fingertips and all of it is free. What you read there will be what I do and use in my day to day woodworking. Remember, we don’t sell any of this information and the tool advice does not produce income from selling tools or taking sponsorship or free goods from makers and suppliers. We are completely independent. This keeps our work clean and wholesome. Also, if you are a machinist only woodworker, this site is for you too. Rarely have I met a machine-only woodworker who understands hand tool methods with any real depth, and that’s understandable. What I am talking about isn’t the general knowledge of what a plane or chisel does, but the minute ways we adjust the tool settings and more importantly the flex of our arms and hands in the manipulations we do throughout their use. Oh, and I do include 95% of professional woodworkers and furniture makers in the machine-only realms. I don’t say this to be antagonistic, unkind, elitist or self-promoting. As it is with many things; when we think we have arrived, we tend to close off to other things, influences, thinking there is nothing more to be learned.

It’s nothing these days to spend hundreds of pounds on equipment based on the advice of some ‘expert‘ just to sharpen a chisel or a plane, but even if you buy a chisel that arrives sharp, within an hour of use it will need resharpening to restore the edge enough to cut wood. For us, the use of disposable tools isn’t really an option. Even though saws might only cost £7 to cut your wood, these are disposable tools designed not so much to cut wood but to keep you coming back to buy another and another and another. In the beginning, you, starting out, this might just work, as will the sharp and well-set plane and the sharp chisels, but all the edge tools and saws must be resharpened regularly and this should never be neglected if you are to get good results in your making. And don’t be sold the line that says, “Works straight out of the box!” or the buyer comments that say so. That’s fine for an electric kettle or a camera. It’s possibly right and even likely to be true with some companies, but the person sending out a plane will not be there after an hour of using it to resharpen and set it for you. One slip of a lever or a twist of the “turny-thingy” does not reset the alignment of the blade or the depth of cut to restore the previous settings, and there is no reset button or default setting to return to. We have to gain the kind of knowledge needed to tweak with a pinch or a twist as early as possible. I spent years writing my book, Essential Woodworking Hand Tools, to cut to the core of tool sharpening, use and ownership. It was less about owning the tools and everything about owning the knowledge on how to maintain them, so, how to sharpen them and use them efficiently and effectively is key to all future.

Okay, we need to know these things to build and undergird a new future on the simplicity of simple sharpening. My follow-on from this will be the nuts-and-bolts stuff I do in my everyday working. If I teach you nothing else, we must get the simple art of sharpening our tools down first.