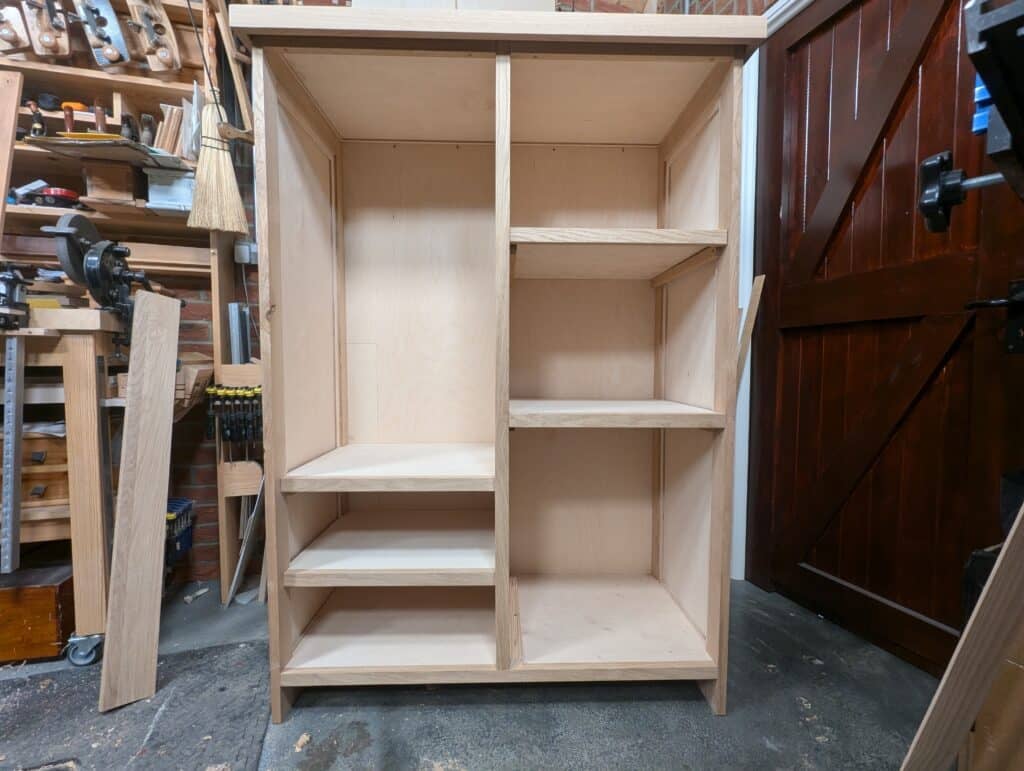

My new project is coming together well. I’m altogether convinced of its many merits and thrilled to be near completion. Already a couple of friends have said, “I want one!” Followed by, “It’s perfect for….. and for……”

The door swung freely to and fro the first time I tried it. Three brass hinges synchronised the movement and a slight friction squeek from one hinge told me the pins were tight but not too tight. Setting recessed hinges ensures nothing will shift long term but the work requires exactness. I got it first time and a sharp chisel took good care of each hinge setting. One of my handmade router planes, a smaller version set the depth for the guaranted flatness and neatness I wanted, took over from the chisel work and sped up the process because I can use all of my own power and directness. I’ve used twelve plywood panels made from birch. The final wardobe is one of the most solid and dependable I have ever made. In some ways it’s been an experiment. In others there is nothing experimental about it at all. The difference in this piece is the hybridising of materials and traditions to create a complete flat-pack product with a built-in longevity to outlast generations of users even if they dismantle and trans[port it dozens and dozens of times in several lifetimes. I’m happy!

Can plywood last as long as solid wood? It can and it can’t. The main consideration about plywood as with any other engineered board revolves around material particle breakdown. Though wood can and often is the prime material used in manufactured boards or sheet goods, the integrity of many materials often becomes compromised over long-term exposure to day to day moistures in the atmosphere causing the material to expand and contract even when in most cases that might only be minimally and much less than in wood. This then results in a breakdown in the integrated composite fibres that generally rely on different types of resins and adhesives for cohesion. For better furniture making, plywood has been highly regarded for its long-term reliability but in recent years high demand and mass manufacturing competition and the resultant cost-cutting has led to look-good products masked by an outer veneer. It’s best to get to know your supplier knowing their sheets come from a quality maker. They’re out there.

I do understand the reluctance people have to trust their work to an engineered panel usually held together with glue but the glues are better and more resilient than they have ever been. Plywood is made up of multiple veneers where each of the the thin layers is laid so that the grain direction of each layer is placed at 90º to the adjacent layers. This building up of layers creates a strong and durable sheet composed primarily of solid wood. The adhesive used on high grade plywood and the veneers used or of the highest quality but on low-grade plywoods the outer layers of veneer exposed to the outside front and back often separate. This separation exposes the inner layers to the issue of moisture absorption leading to further breakdown and disintegration in the long term.

For both indoor use, plywood resolves many issues including shrinkage or expanion, strength needs and expansive wide and long panelling. Buying good or top quality plywood is always key to longevity. Choosing a maker with a good reputation is not always easy as often we have no knowledge of the maker. Knowing your supplier can be the same way but due diligence in your enquiries will help. The plywood I choose is what we term water and boil proof ––WBP. Plywood is now a traditional material. Lower grade plywoods can have overlaying in the core layers which affects the evenness of thickness and also puts pressure on the adjacent layers along with the outer finished and sanded surfaces. The lower grades commonly have voids between the layers which causes problems in one way or another down the line and is unacceptable. The birch plywood I mostly use has none of this and all the layers including the ever-important outer layers are of near equal thickness. This means that I can, if necessary, plane or scrape even these outer surfaces. Decorative faces veneered with an ultra-thin skin rarely have this depth of thickness and might well be little more than the thickness of a sheet of paper.

My enjoyment in my work comes from trying and trialing new things, experimenting and discovering what can and cannot be done. We tend to think that sheet materials don’t expand and contract but they do. Stability of wood varies according to the wood species and this results in what we call wood movement. Plunge a dried down section of 6″ wide and half-inch long maple into a bucket of water and leave it for 24 hours and the maple will have expanded by over a centimetre: a good half inch. Wood movement can mean many things to us but mostly its the expansion and contraction that impacts our work. My tight tolerances in some of the cabinets in Sellers’ Home pieces meant I had to go back in and ‘fix’ problems like doors and drawers sticking or catching. I mostly ecected this and especially with maple or sycamore because these two culprits need extra space to expand into. This si the reason we should not decrease moisture levels to a fanatically low level. 11-15% is usually good for most homes but I am cautious in this because it also depneds on where you live, how many kids take shopwers and whether you create steam in your cooking. These can be measured with a basic low-cost hygrometers magnetised to different parts of your home. A hygrometer is not the same as a moisture meter which measures the amount of moisture already existing in materials like wood, bricks, plaster and so on. My experiments of some 25 years ago on the expansion of wood through immersion and allowing the same to reacclimate in the atmosphere it would eventually spend the rest of its dried life gave me experiential knowledge I could rely on in my making furniture for the rest of my life. Rather than just reading what some author wrote as his or her thesis but that bore no resemblance to much of any kind of reality I discovered knowledge that would be mine forever.

Many things I do may never have been done in this or that particular situation, they can be absolutly never done before I do it, but they can be adapted to give me something completely brand new. In this plan for a different panel board lipped or framed with solid oak and conventional and unconventional methods for creating doors and framed panels or edge lipping with true substance came not to compete with machine makers but to equip hand tool makers. Of course, I am not selfish. If machinists want to use the methods `i used they can go ahead. i wanted to be advantaged by the sheer span and stability plywood gave me but still rely on my highly trusted and efficient hand tools. I also wanted the pure exercise and mental reliance on making by hand that cannot be had by the alternative methods of machining. using my system gave me the pure delight of adaptation and adoption of a material that could be worked and managed by hand methods along with mortise and tenon joinery, dovetails, etc.

How confident am I that the glued surfaces working as laminations will last? Well, I am 75 years old in three months. I have used this birch plywood since I was 15 years old and it has never failed me. But `i have also dismantled pieces with plywood in them that are much older than that, perhaps a hundred years old, and this plywood was not WBP. Think about a Stradivarius violin or cello. There are about 20-30 pieces in such an instrument. Did you know that that there is but one joint connecting the neck to the body and all of the other pieces are simply glued and clamped in place until the glue dries? He was actively making unti, his death in 1737. All he used as an adhesive was animal hide glue. 300 years since he glued up his pieces and they are still together.