. . . for better health, strength and stamina. Wood works for health and welfare when your hands or on the right tools, and you use all of your own energy and skill in the doing of it.

Of the sharpening of many edges there is no end and yet, every tool I ever bought online or from eBay, hundreds of them, I never received a tool that came to me sharp. Such is the consistency of this, it made me stop to realise how tools are used and used to such neglectful levels, the reason they end up being sold on is because they didn’t work for the new user/owner. As such, the simply refused to make one more cut. Another funny thing, if it wasn’t so sad, is that even dull tools still cut for a substantial amount of time before they actually reach this stage if enough force is used. Hence, the belief that you need to ‘power-down‘ from above with all your “upper-body weight and strength” and so the planing bench needs to be low enough to achieve that. That is how we ended up with such ridiculous recommendations for low benches to work from. I’m not a tall man, nor am I a bulky mass of muscle and big-boned weight! That being the case, as with most lighter weights, I tend to strategise my moves at and around the workbench. Subconsciously strategise and plan moves ahead of tasks, consider the best ways to cut and plane and fit my components in the vise, on the bench top and so on. Engaging brain power is the true essence of power woodworking. Accept no substitutes.

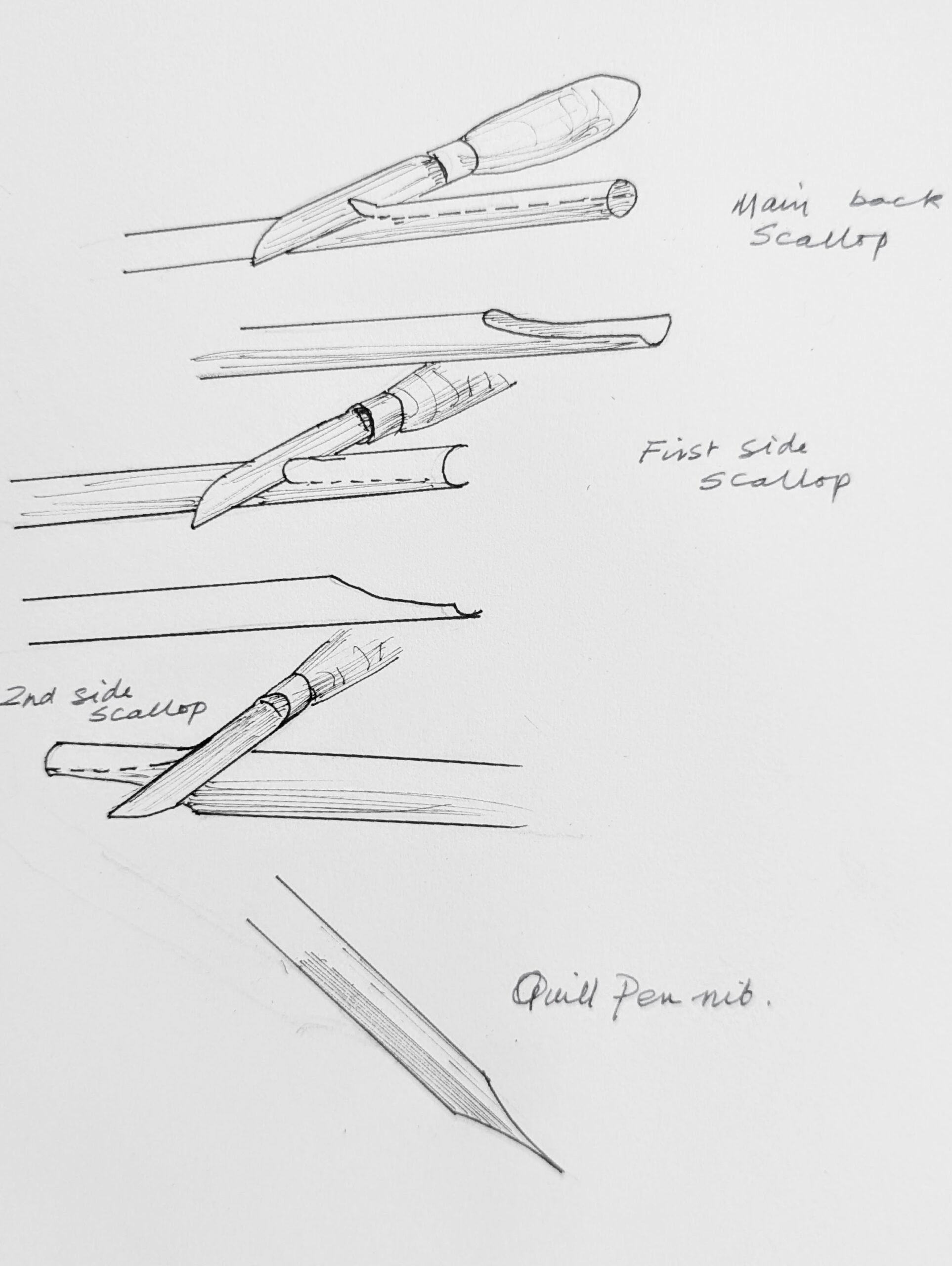

I think it goes to show that one of the most basic skills on the planet, sharpening, owned by all at one time, was the basic skill of honing a decent cutting edge. I carry a knife in my pocket everywhere I go. I wouldn’t be without one. Mine’s a single bladed lambs-foot pocket knife with a rigidly good blade that, though not a lock knife, stays. I don’t think any man in my youth ever left home without a decent pocket knife. In the UK, we call them penknives. Pen and pocket knives are one and the same. Why did we call them pen knives? Because back in time, the penknife was used to sharpen the feather quills used for dipping ink pens to write with. After a while, the sharp point of the quill would turn or become damaged and lose the crispness needed for fine writing. Three quick scallops gave you a new point to write with.

Seeing the neglected edges on so many edge tools always makes me wonder what kind of brutish person was that last user? What power would it take to effect that last cut, if indeed it did cut. But over all the years of teaching and training students through the schools I’ve started and run, sharpening is the single most misunderstand with regards to its importance, how to actually do it and then when or how often. On another note: buying secondhand tools in a large number through many years, I never had a single cutting edge that came with two bevels; in fact, they always had a macro-camber and never a hollow grind. The clues here are hollow grind and second bevel––no matter what name you choose, secondary, micro, etc, the two bevel system came by necessity.

Hollow grinding demands a second bevel, even if the second bevel is adding a steeper, but very narrow hollow grind angled lower to the wheel. Back in the 1950s, Black & Decker came out with an ultra-cheap 6″ grinding wheel. Unlike the 18″ diameter sandstone grinders of old, treadle- or hand-powered, that large ground bevel a barely discernible hollow, these grinders ground a hollow that looked the same radius as that of the inside of a tin can. That being so, you had no choice but to refine the edge with a second bevel to make it viable. Mostly it was the early days of a ‘man thing’ where owning something like this meant you could ‘take care of your stuff‘, like garden shears and lawn mower blades, scissors and anything needing a sharp edge. It was a mechanical way to move things forward.

Any cutting edge wears to dullness in a fairly short time in the hands of a user/maker. How often he or she sharpens depends on how high their self demand is. Because I don’t use any kind of power planer or a tablesaw, chop saw and such, I probably sharpen many times more than most without being excessive. That’s because I spend many hours planing hardwood from rough-sawn to true and four-square to work with most days. My new piece has 40 pieces of oak in it. The bandsaw rips most of the rough cuts in long, deep rips, otherwise anything over an inch thick becomes prohibitive. But stroking the faces with a sharp plane is always uncompromised sharpness. Otherwise, it’s hard, hard work.

Planing the wood, oak especially, I think, is almost always pure joy. Perhaps it’s because it is so very easy to plane and scrape, so responsive, I suppose, but it also has so much character and the appearance changes under every stroke taken. How can this not enrich any maker’s life. People will always say to me how much they “love wood”, when the reality is that all they actually get is the merest snapshot with the wood beneath its plastic coat of some kind of varnish. It’s true too that rarely will they actually touch the real wood either, let alone split, plane and saw it. It’s also a sad thing and I am sorry to say it, though they may well believe differently, that is also true when a person makes using machine methods only. Sensory perception is magnified a hundred times simply by using hand tools, whereas machines mainly minimise and even by necessity eliminate the deeper involvement hand tools demand. For safety reasons, machining with some of the most dangerous machines available, you must wear protection for 95% of tasks. I know many if not most woodworkers with a machine setup do not, but that’s up to them. It’s their health and safety.

If running or cycling moves runners and cyclists to push themselves along concrete roads enveloped in hard core, heavy-duty traffic, then planing wood for a workout in a clean and virtually pollution-free environment like mine has to top any of that. The icing on the cake is to hand cut mortise and tenons and make machineless dovetails with a gent’s saw and a couple of chisels. For me, nothing comes close, and I attribute that to the sharpness of my cutting edges, the confidence I’ve gained from decades of doing just that, and the assurance that this or that is always going to come out right because I worked on the foundation of my craft. The extreme opposite of that for me would be going to the gym. When I work, the result is always a fine piece of artwork, some very useful and highly usable muscle on permanent tap, muscle maintenance, lots and lots of brainwork and an overall healthy way of living to work and working to live. I think too that I have no need for offsetting boredom by wearing headphones because nothing I do in a day is boring. In my sixty years of working with hand tools, I never knew a day without work. My dad said to me when I was fourteen and choosing my vocation to become a joiner making furniture and joinery, “If you can work with your hands, you will never know a day without work.” That has proven to be true. I chose the road less travelled in my choices simply because I loved the freedom handwork always gives me. I’m glad I wasn’t “lucky” in any way and chose my calling according to that which no one speaks of any more, my vocation.

In January, I will be seventy-five years old. To have reached this age with the level of fitness I enjoy seems to me at least to be remarkable. My hands still seem acceptably steady, and in eight hours standing and working at the bench, I rarely if ever sit down to work on anything but the occasional sharpening of my saws. When I held my sixteen-person classes in the USA, every student bar none sat on a shop stool throughout each day. This impossible woodworking position held them captive, but I understood the habits of a lifetime started back in school, on through their higher education and into the workplace filled with desks and chairs. But, interestingly, by the end of a week-long class they all shifted and without my saying a thing they’d shunted their chairs away in favour of movement, body and hand-eye alignment. What made the difference? Two things, they developed muscles they had rarely if ever worked before and matched them more readily to the diverse tasks minute by minute woodworking requires, and then their work became more accurate in many ways, including the precise and accurate manipulation and functionality of their bodies.

Hand tool woodworking is obviously the higher-demand woodworking, it’s true. So many neck, eye alignment and hand, upper arm and shoulder movements along with body flexes follow a million ways we tension and pretension our muscles and minds to make the tools work. Trying to explain how good this is for the mind and body, our physical body, if you will, would take me a lifetime to explain, but I try my best in my blogs. The best way to learn of these things is in the working of hand tools. When you get to 75, and I may well be long gone, you may well whisper, ‘Thanks, Paul!’