Part I: Moxon to Nicholson

By Matt Cianci, the SawWright

I started writing “Set & File: A Practical Guide to Saw Sharpening” in 2015, but the background work started long before that in the early 2000s. For me, learning to sharpen saws was trial and error, and there wasn’t much to guide me. I looked for written instructions but was always left wanting. I had no teacher to direct me, and whatever texts I did find seemed vague and superficial like the author didn’t really file saws all that often or at all.

That said, during the last 20 years or so I’ve collected a small library of books that describe saw filing and care. The story begins with Joseph Moxon, of course, and continues through today. Some of these books are fascinating and entertaining, others are not, but they are all important to me. While reading and re-reading them over the years I started creating a mental list of what they got right, what they got wrong and what they missed all together.

As my book begins to make its way out into the world, I thought it might be fun to share some of my favorites. For simplicity, I’ll present the books chronologically as they were published, and separated into three general age groups: Really Old (authors wore wigs), Old (authors wore jackets and ties), and New-ish (authors wore shorts).

This is certainly not how I discovered and read them mind you, and this list is by no means all inclusive. I’m sure there are works out there I am not familiar with, and while I’d like to say that I have read (and know) everything there is about saws, my wife is sitting next to me on the porch as I write, and she won’t feed me dinner if I act up. So please do suggest other books or articles in the comments that you know of and find relevant. She would greatly appreciate you keeping my feet on the ground and my head out of my…..well, you know. 😉 Here we go…

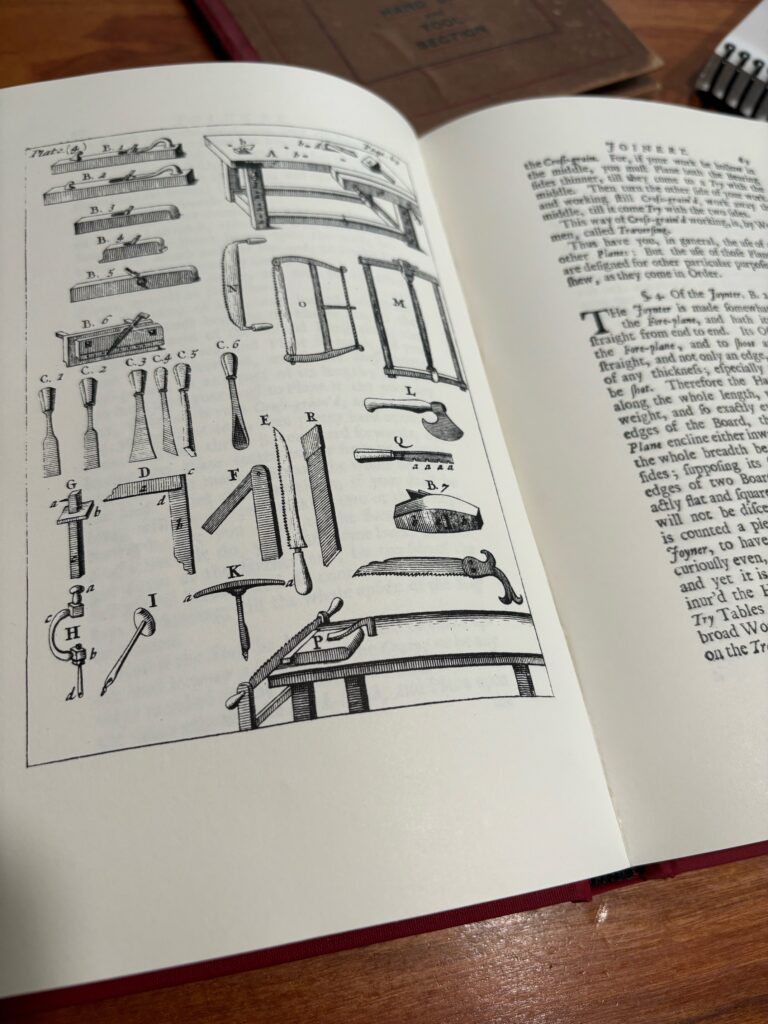

Mechanick Exercises by Joseph Moxon, 1680(ish)

This is said to be the first book on woodworking written in English, and it is one of my favorites. It has a tangible charm in its prose, which is relatively simple to understand and (mostly) clearly written. And I love the old English long “s” that looks like an “f.” For some reason (probably linked to my warped reality), I like to imagine Moxon narrating the words to me with a slight speech impediment and actually pronouncing the long s’s as f’s like they appear. I think it adds to the charm and helps distract me from the fact that for all we know everything in the book is completely made up. Regardless, Joe does include a brief description on how to sharpen a saw in Section 26 of the Joinery chapter.

He writes, “…with a three-square File they (the Workmen) begin at the left hand end, leaning harder upon the side of the File on the right Hand, than on that side to the left hand; so that they File the upper side of the Tooth of the Saw a-slope towards the right Hand, and the underside of the Tooth a little a-slope towards the left, or, almost downright.”

Pretty clear, right? When I first read this, I twisted myself into a pretzel trying to find “the underside of the Tooth.” What, for the love of King Charles, is the underside of a tooth?!? No matter how many ways I turned the saw end for end I couldn’t find it. With that cleared up, he moves on to setting the teeth, which makes only slightly more sense. It’s pretty clear from Moxon’s use of ‘They,’ that he wasn’t talking about himself filing saws, and thus was established the important precedent of fancy white guys spouting off about things they know nothing about. Despite this, it actually is a fascinating early look at saw sharpening. It certainly raises more questions than it answers, but it’s just about as close as we can get to T=0 for saws. My first copy of Moxon was acquired years ago in a paperback reprint from my friend Gary Roberts at Toolemera Press, and I believe it is still available. I have acquired several other copies and reprints over the years including the first Lost Art Press book from Mr. Schwarz, “The Art of Joinery,” and the later Lost Art Press full-text version so I can learn bricklaying in my spare time, too.

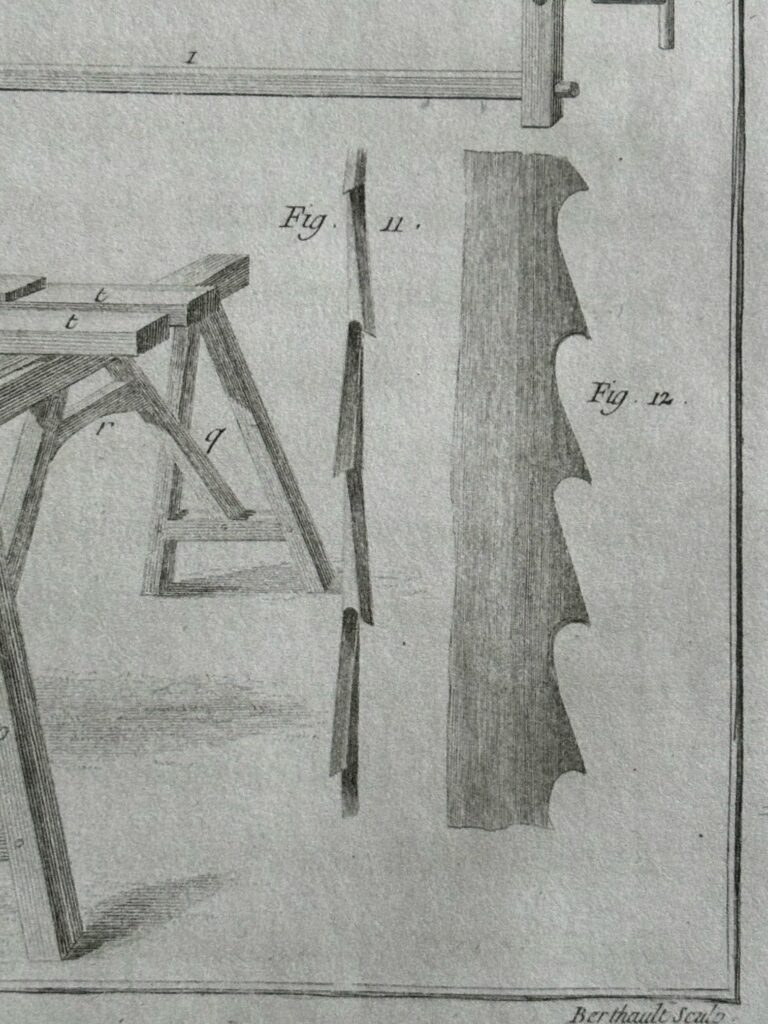

With All the Precision Possible by Andre-Jacob Roubo, late 1700s

Across the Channel and a few decades later comes A.J. Roubo, hellbent on setting the craft record straight and not letting some English puddle chaser set the standard for woodworking. Like most, I didn’t read Roubo until it was translated into English a few years ago by LAP, but when I (we) finally could it did not disappoint. “Wow” is all I can say. What struck me most was Plate 5 regarding “The Sawing of Wood.” In the lower right-hand corner, tucked between figures 9 and 12 is a revelation. Clear as day are shown a row of teeth with alternating bevels at their points: fleam!

Roubo (translated) describes filing these teeth as such: “They are not filed squarely, but on an angle, each tooth in opposing direction one to the other. One must note that this angle is not present except in the leading edge and that the base is at a right angle, or squared, with the saw.”

Over the years I have been intrigued by an argument that I first learned of from Roy Underhill (if I recall correctly) that the joiners at Colonial Williamsburg do not file their saws with any tooth bevel, or fleam, as it is also known. The reason as I understand it (in chatting with the joiners at the Williamsburg cabinet shop) is that they cannot find any historical evidence that saw teeth were in fact beveled in the 18th century, and that they simply filed their saws straight across and with a raked back tooth for crosscutting. This argument has never made sense to me. It seems like the kind of logic that would suggest colonial English folk didn’t put jam on their toast because we haven’t found any toast from that period with jam still on it. Saws, like toast I would assume, would tend to get used up and erased as evidence, right? And tooth bevel is not all that complex as technical innovations go, either. For me, Andre ended the argument with Plate 5, but I imagine that 18th-century Englishmen are not so inclined to take direction from the French (unless you count plagiarizing their work…Moxon!). It is worth mentioning that Roubo was describing how a pit saw was filed, meaning a large frame saw for turning big slabs into usable planks, which curiously is a ripping operation and would not seem to benefit at all from a beveled tooth. As far as I can recall he doesn’t describe saw filing anywhere else, nor ever specifically the smaller saws used at the bench. And did AJ ever file a saw himself? He must have if he was a trained joiner, right? This certainly lends more credit to his saw descriptions in general, but it is clear that like Moxon this is not a description of how he files a saw, but how “they” file a saw. Similar to Mechanick Exercises this description is far from helpful, but it’s a solid second showing. Either way, it’s the oldest and most significant evidence that fleam was in common use on saws in the 18th century, at least in France.

Mechanic’s Companion by Peter Nicholson, 1812

To round out the early period of notable saw writings comes Peter Nicholoson some decades after Roubo and comfortably back across the Channel, thank goodness. He is said to have been a trained cabinetmaker so in addition to being an expert drinker we can confidently assume he had first-hand experience to convey about saw filing.

But no such luck. Pete does share some tantalizing descriptions of saw teeth as a consolation, but he seems to have prioritized a description of using basil when sharpening your plane iron (an odd lubricant if you ask me) over even the slightest mention of what kind of herb (or other medium) he recommends if your saw becomes dull. This is an odd oversight to say the least.

The chapter on Carpentry actually opens with a description of saws and he writes, “Some saws are used for dividing the wood in the direction of the fibre,…others are only employed in cutting in a direction perpendicular to the fibres…the former case requires the front edges of their teeth to stand almost perpendicular to the line passing through their angles…for otherwise the points of the teeth would run so deep into the wood, as to prevent the workmen from pushing the saw forward without breaking it.”

Nicholson is describing tooth rake, and in doing so provides the first written assertion I’ve found that saws need to be filed in different ways to accommodate either ripping or crosscutting operations. He continues in the Joinery chapter with specifics on types of saws used in furniture making and what kind of tooth spacing each saw should have. This is where things get really exciting, and by exciting I mean: Remind you of why you love your table saw.

Pete shares that, “The Ripping Saw Is used in dividing or splitting wood in the direction of the fibres; the teeth are very large, there being eight in three inches and the front of the teeth stand perpendicular to the line which ranges with the points.”

If you can do the math, that means this is a 2-1/3 tooth per inch (TPI) handsaw with zero tooth rake. Converted to points per inch (PPI) this is 3-1/3, which is fair to round up to 3-1/2 points. That’s one hell of a rip saw. If you’ve ever tried ripping with such a saw in something like oak or any other hardwood, you likely have a truer appreciation for the aforementioned drinking. I first acquired this book from Toolemera Press years ago in paperback. It may still be available there, but it has now also been reprinted by LAP with a proper Smyth-sewn binding and hardcover.

Next, in Part II of this three part series we’ll take a look at information from the golden age of western saw making, including trade propaganda and crazy people throwing saws off of roof tops. Stay tuned.

— Matt Cianci