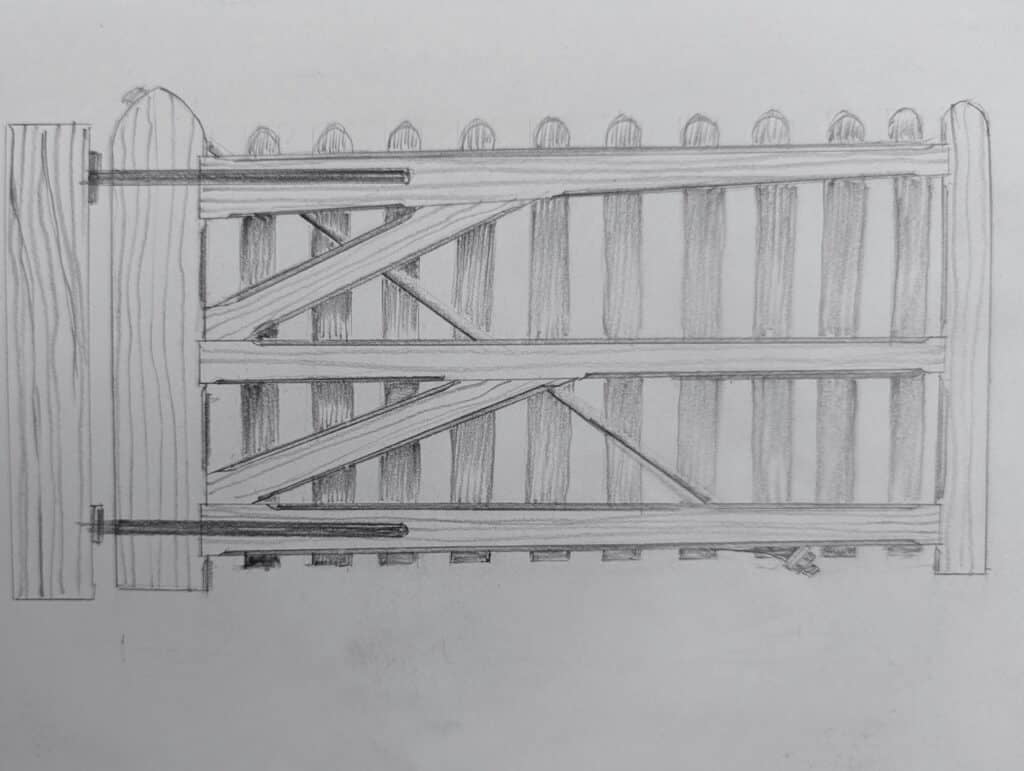

People open them and leave them to slam, saying they closed the gate but they didn’t close it. I think a well-made gate deserves respect for its maker. This gate, ageing now, has wear and cracks that tell me things that others miss when they pass through it, leave the gate to slam shut and shorten its age by a third. Well, still, it’s holding up fine. I opened it and closed it without leaving it helplessly to slam because, well, again, I cared. The gate leads to a pathway following along the rim of a beautiful lake people visit for peace and recreation. Two people came to swim while others sent their dog after an orange ball. I spent some hours there contemplating future hopes and aspirations over the last four days. The people who swam swam a long way out until I could just about see two dots and when they came back they asked me why I was drawing a gate. I said I felt it needed recording and putting somewhere safe so we don’t forget the maker whose name is already forgotten or unknown. It would be a neat thing for someone to make another, I think.

I have written about the loveliness of garden and fieldgates made of wood before. A few sections of rough-sawn oak with calculated rails set at sdiminishing spacings to keep the lambs in as new-borns in Spring. Just a humble gate made by a man most likely. He’d be a man no one knew outside of his village and the carpenter’s workshop tuckeed away in some quiet corner. He might have marked his work as men often did with nothing more than a simple mark somewhere tucked away in another quiet corner of the gate he’d just made. No one knew of such things as the humility of a man-maker who chopped out his mortises knowing others would let his gate slam-to instead of closing it to save stressing the joints and splitting the wood somewhere. You know of such things when you make a gate or door.

The oak gate needs no finish to it, for finish will hold moisture in to ultimately prematurely rot the wood. A pine one made of heavy sections stoutly framed has tapered rails in like fashion to save weight to the free side. The free stile or post too is slimmer still by half and then, look, see how the threaded rod passes through at so steep and long a rake angle, pulling to take the strain and give additional future adjustment to raise the free stile if the wood should sag over years to come. So small a thing made so with longevity and forethought in mind for others to own and not the man maker beyond his then three-score-and-ten.

So we look at the deeper things in making. these men built with forethought anf anticipation knowing the North Wales coastal weather that hits with great force every few days and then, often, for days on end. I love that such things were deeply considered. But then I took in the stoppped chamfers that had good reason and forethought too. Were they decorative? Not in the least. Chamfers didn’t just ‘ease the corners’ of gates like this. Not at all. On the top rail, they narrowed the width by a two-thirds span so that water could and would drain off quickly. The main reason for these stopped chamfers was to allow for continuous paint surfaces that would not break continuity on the corners through expansion and contraction of wood at right-angles.

In the past we used to use red lead paint for outdoor projects. We used nit when we made or installed wooden gutters to building before we lined it with lead to catch the roof’s rainwater. Those days are gone but had their roots in the `romans establishing theoir rule in Britain where they could. Funny when you think about. People replaced lead with plastic a million-fold. We have an incredible capacity to pollute, don’t we? When plastic first came out for windows and doors here in the UK, sales reps offered a lifetime warranty without telling anyone what a “Lifetime” was. Since then we understand that the lifespan of plastic windos and doors is around fifteen years. Just a fraction of wood. Hey ho, there you go!

The gate I drew just above is made from Redwood pine. To have a gate live long you must have a regimen of meticulously painting it. If you do that every five years or so it will last for decades but yopu must first prime the wood with primer paint and then go with two undercoats and a top coat of gloss. Oil-based lasts longest but people have erroniously believed manufacturers who say things about the environment abd the washability of water-based finishes as though they are not toxic when they are literally fluid plastic washing into the water systems and watercourses . Hard to know what to do but our influencers and activists are most likely washing their acrylic paint brushes in the kitchen sink whilst gluing their hands to metal structures and pavements with superglue or CA glue (cyanoacrylate glue) which is composed of an acrylic resin. The main ingredient in cyanoacrylate glue is cyanoacrylate, which is an acrylic monomer that transforms to a plastic state after curing. Anyway, there you are.

So here is a fairly basic gate that needed almost no skill to make and we will see how long it lasts as the years pass. I don’t think it is ugly, it just relies wholly on 30 screws and a couple of bolts that hold the hinges to the gate for the gate to hang. Of course, we understand that skilled work is in high demand elsewhere and a garden gate that takes onkly a couple of hours to make provides an economical answer. I’d estimate that it will last a decade or so which is possibky not a bad return on your investemnt. Even a fully jointed one might only last twice to three times as long in the right wood. Anyway, compared to the slate wall three feet thick the gate will need replacing many a hundred times.